Kibble – reading labels, what really goes in it?

In fact, given that you’re probably not an “expert” on pet food, as I suppose I sort of am, this may well have happened to you many times. The fact that it does still happen to me every now and then is testament to just how easy it is to be led down the garden path by canny processed pet food producers, experts of marketing spin.

So, while I do still occasionally, albeit briefly, fall for their marketing sorcery, I have learned a good few tricks along the way to work out what you’re reading, from very basic pointers, to the level of semi-professional label reader. And through doing this, as well as by asking companies lots of questions, by reading Australian Standards from cover to cover, and by heavily researching the topic to the point that it’s actually a bit embarrassing how much I know about processed pet food, I feel quite well placed to explain a few things about it.

Check the ingredients on the pack:

Some kibbles do not even list or name the specific protein they use. Processed dog food is almost always centred around a main animal protein, and we’re led to believe it is brimming with juicy chicken breasts and shiny salmon fillets, as per the glossy photos on the bag, but the reality is quite different.

Although you absolutely should expect to see meat as the first ingredient in any dog food product, there is a little more to it than that. If a company does not name the specific protein they use, this is a big, big red flag. If a business cannot even tell you what animal the meat comes from, there is no possible way they can tell you anything resembling genuine transparency around the supply chain this meat came from, prior to ending up in their food.

There is also a big difference between “meat” and “meat meal.” One is 75% water, the other is basically devoid of any moisture. So while the idea of “meat meal” might horrify you (more on that in a minute), it is almost guaranteed that a food that lists meat meal at the front of their ingredients list actually contains a lot more animal protein than one that lists “meat” in its whole form. This is because ingredients lists are required to be listed by weight, meaning an ingredient that is 75% water is going be far heavier than an ingredient with no water, despite the fact that this water is all removed during the cooking process. Tricky.

What the heck is meat meal?

Meat meal is a shelf stable meat powder that is made from rendering meat and bones not fit for human consumption. It is the same process that is used to separate tallow for making things like soap, whereby the fat and water is split from the meat using very high temperatures. According to their own website, The Rendering Association considers themselves to be a recycling service, above all else, and they acknowledge that plastic ear tags are not removed from heads of livestock before they are rendered to be turned into pet food.

Ingredient splitting is a trick:

Sometimes we see both meat AND meat meal, and this is because of a little thing called ingredient splitting. The function of ingredient splitting is to give the illusion of more protein. In the case of splitting say, chicken, into a fresh version and a dry version, the result is that now it appears twice and, to the untrained eye, looks to be much higher in chicken content (perhaps twice as much) than it really is. When actually it is just water weight and no additional chicken.

The reverse is true of less desirable ingredients like, for example, legumes. Splitting in this context enables low nutritional ‘fillers’ to appear smaller in weight to the so-called core protein. Often we will see as many as four or five different beans and peas, the nutritional value and function of which are incredibly similar, at least in this context. The reason for this is that each serve of the 5 different beans weighs significantly less than the sum total, and also less than the meat ingredient in number one position.

How much ‘meat’ is really in there?

We aren’t meant to know! More than likely, if you see multiple very similar ingredients they have been selected strategically so that meat is the first ingredient. You may also see the same ingredient in a few different forms. This is common of things like peas, which may appear as “peas,” as well as things like pea protein and pea flour. All peas. Lotsa peas.

According to the Australian Renderers Association, as well as pet food industry insiders I’ve personally spoken to, it is typical for kibble to contain around 20% meat meal or less, and high end ones cap out at around 30%. This is partly due to the high bone content of meat meal, as well as other things like cost and the functional necessity for starches to tie the ingredients together.

What about all those carbs?

It’s not at all unusual for a dry pet food to be more than half carbohydrate based ingredients, like grains and legumes, which is necessary to form the biscuit dough. This is incredibly high, keeping in mind that dogs and cats have no mandated carbohydrate requirement at all.

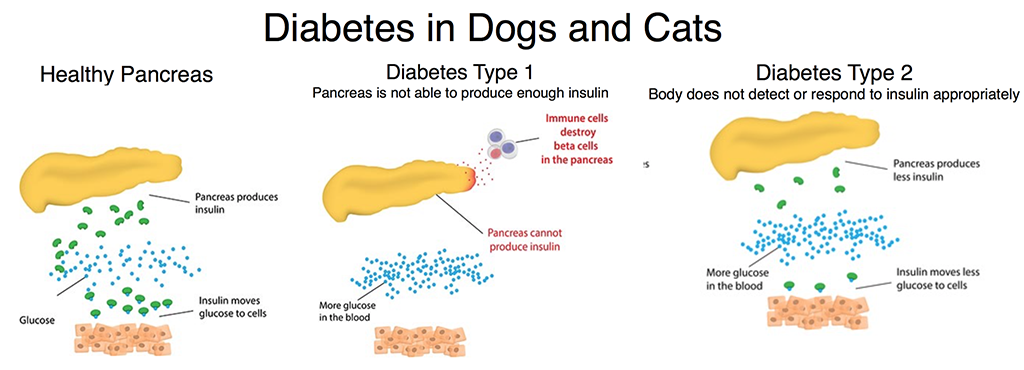

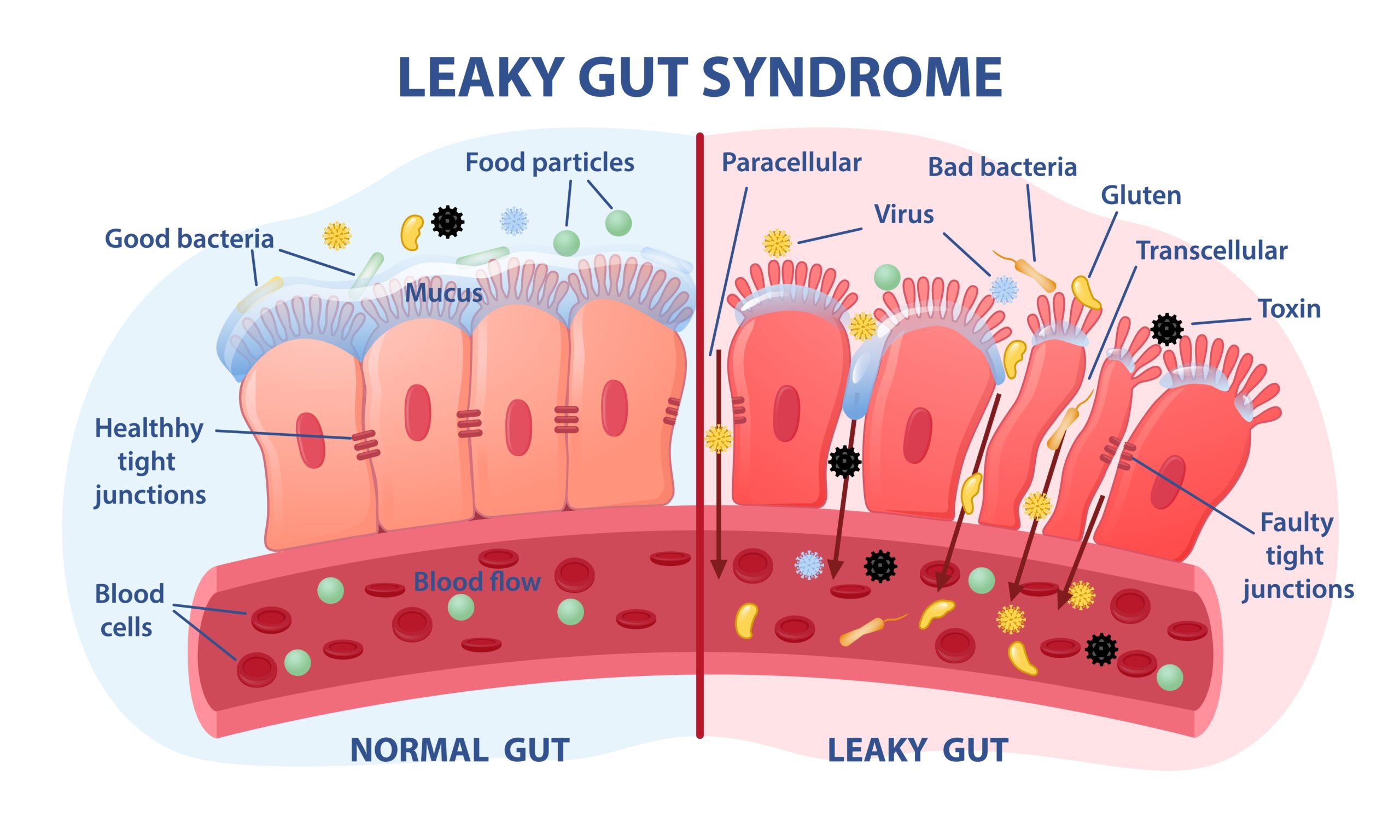

The problem with starchy carbs is they quickly break down into simple sugars that enter the bloodstream, spiking blood sugar levels. This triggers the pancreas to release insulin, a hormone that tells our cells to absorb the blood glucose for energy. Because this all happens very quickly with highly processed and high GI carbs, dogs can feel hungry more quickly, while also storing excess glucose as fat and over time risking diabetes, heart disease and obesity. Yeast infections and cancer both love sugar too, so the danger here speaks for itself.

What about all the so-called ‘superfoods’ and ‘vitamins’?

Aside from some additional fats (all the fat is removed from the meat meal, remember), kibbles contain artificial flavours (because there is no natural taste, and to make it smell nicer to us), and minuscule amounts of ‘superfoods’ (which sound amazing in the advertising), and a vitamin and mineral premix.

Is it complete and balanced?

Where vitamins or superfood quantities are so small, they don’t even register as a percentage. As a guide, if they are below salt on the packaging, this means less than 1%.

These vitamins and minerals are usually cheap oxides, sulphates and other inorganic synthetics, rather than actual nutrients as they appear in nature, or even high quality isolates. The bioavailability of these is questionable, but studies have shown they are poorly utilised compared to higher quality synthetics, let alone nutrients in actual food. These synthetic nutrient supplements are essential to meet the required nutrient levels in the standards set out by the powers that be, because the repeated high heat treatment that processed food undergoes degrades any actual nutrients so severely they are largely absent. Importantly, it also enables manufacturers to use the term, ‘Complete and Balanced’…

Once all of these ingredients are mixed into a dough, it is then pushed through an extruder, which uses heat and forms the biscuit shapes. It is then cooked, and often cooked again, before being sprayed with flavours.

The end result is a product that can sit on the shelf for years before your dog eats it. There is no requirement to state a date of production, only a batch ID that is meaningless to consumers, and a used by date. Due to the self regulated nature of the Australian pet food industry, as well as the seriously relaxed guidelines in the Australian Standard that governs the marketing of its products, the label on a bag of food can be designed in a way that conceals much of what we’ve just discussed.

But the packaging looks great!

Bags often contain images of foods so premium we might eat them ourselves, emblazoned with a featured animal protein name, and sometimes even a bold claim of as much as 70 or 80% meat. When the reality is that this number includes a ‘rehydration factor’ of x4…remembering they can call meat meal ‘meat’.

These marketing tactics are governed by the voluntary Australian Standard for the Manufacture and Marketing of Pet Food (AS5812), and it acknowledges that dry pet foods are “typically cereal based.” Despite this, the standard permits food to be named after a meat protein while only containing as little as 5% of the named protein, and it doesn’t actually have to even be the main meat protein if the word “with” comes beforehand. If you’ve noticed the recent trend of referring to a food as being with REAL beef, this is why. The “real” is a distraction from the “with” – because really, what other sort of beef would it be?? This standard also states that “justification of content claims, when using dehydrated ingredients, shall be calculated on a reconstituted basis using a recognised conversion factor.” In layman’s terms, what this means is that a claim such as “contains 70% meat,” will have had a rehydration factor of x4 applied to any dry meat ingredients, meaning that in fact it contains only 17.5% of a highly processed and heat treated scrap meat powder. It is totally permitted, arguably encouraged or even mandatory, for them to multiply this portion by 4 and advertise a hypothetical rehydrated percentage, even though it never actually existed in this food.

This would be sort of ok with me if everything was calculated using rehydration factors and we were comparing apples with apples. But they’re not.

And that brings us to the nutrient panel. You’d be forgiven for looking at the nutrient panel on a bag of kibble and thinking “26% protein! Amazing.” But what we need to remember here is that this percentage refers to the finished, dry product, so it is a very concentrated figure on account of all the water having been removed – as opposed to the claim on the front, which has had all the water added back in using “rehydration factors”. These companies pick and choose how they will inflate figures in the way that best suits them and makes their product look better, and as a result risk totally deceiving consumers. Best of both worlds, eh?

Because it is not normal for food to be completely dry, these nutrient panel values are not really comparable to what we are used to seeing. As a result, they often seem high, while actually being very low. While a fresh meat product might advertise a seemingly meagre 15% protein, the dry matter equivalent of this (ie. the percentage of protein once all water is removed) may be as high as 50%. Almost double the actual protein content of the processed food. Another thing to note is that there is no requirement to list a carbohydrate percentage, so most pet food brands choose not to, and many will decline to tell you if you ask (which I did, many times).

There is much more I could say on this topic, but the key point to takeaway is that these foods are almost always labelled and marketed in a way that intentionally has pet owners in a tail spin trying to navigate them, when ultimately the vast majority are extremely similar.

In summary:

The lack of transparency in the processed pet food industry is something I find deeply problematic, and is compounded by a complete lack of mandatory regulations. A few things are certain though; these foods are all made from ingredients that are totally unsuitable for dogs, they are all heavily processed and repeatedly exposed to high temperatures, they are all supplemented with synthetic vitamins and minerals in order to show they contain ‘adequate nutrition’, and they are all permitted to sit on a shelf for as long as 18 months before being fed to your pet.

No amount of labelling gymnastics will change these facts, and this is really all you need to know.

(In this article I refer to “processed pet food,” “dry dog food” and “kibble”, by which I mean the typical, biscuit based dog food that we find at the supermarket.)